As neonatal care has improved dramatically, so has the number of extremely premature neonates who survive. The paradox of this success is the growing cohort of children who develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and require long-term respiratory support. This has resulted in an uptick in pediatric tracheostomy placement. But data describing ventilation-associated outcomes has been scarce, leaving unanswered questions for physicians and families.

To address this gap, a study of children under age 18 who underwent tracheostomy at Children’s Health℠ between 2015 and 2021 found that more than half of BPD patients requiring tracheostomies successfully come off external ventilation within five years. Many are decannulated between 2.5-3.5 years of age.

The study also found that, while children with BPD were likely to need mechanical ventilation for longer than those who had received tracheostomy for other reasons, they were also more likely to achieve ventilator liberation and decannulation. The presence of pulmonary hypertension – regardless of whether the patient had BPD – was associated with both a longer duration of ventilator dependence and a shorter time to death.

Study contributors

The study was conducted by physician-researchers at Children’s Health and UT Southwestern and published in Pediatric Pulmonology. Co-authors include:

Andrew Gelfand, M.D., Medical Director of the Integrated Therapy Unit at Children’s Health, and Professor at UT Southwestern.

Stephen Chorney, M.D., Pediatric Otolaryngologist at Children’s Health and Associate Professor at UT Southwestern.

Folashade Afolabi, M.D., Pediatric Pulmonologist at Children’s Health and Associate Professor at UT Southwestern.

Together, they offer insights on optimizing the care of children with BPD-necessitated tracheostomy as they move toward a healthier life.

What need did this study fill?

Dr. Chorney: The first thing parents want to know when we talk with them about tracheostomy is ‘when can you take it out’. Our study provides data we can share with them about what to expect based on outcomes of children with similar medical complexity over the past 5 to 10 years.

What has changed in the ventilation strategy for these fragile young children?

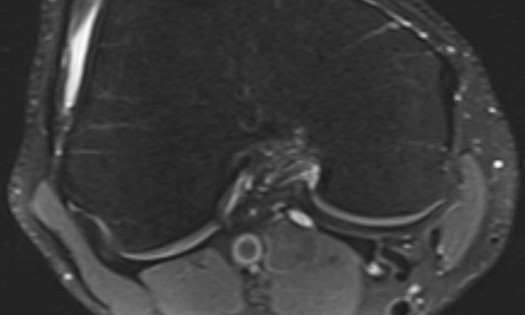

Dr. Gelfand: For a long time, the standard approach was 40-60 shallower breaths per minute. Based on recent research, we’ve landed at 20-40 longer, deeper breaths per minute. The larger tidal volume and higher positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) keep a baby’s lungs inflated for longer periods, which gives each of their alveolar units time to adjust to the pressure change. This promotes more uniform lung development over time.

Much of a child’s journey to decannulation happens outside the hospital. How do you help families and caregivers prepare?

Dr. Afolabi: Caring for a child on a ventilator at home is daunting – and supporting a child while their lungs grow and develop can go on for a long time. Our team emphasizes training and education so parents and other caregivers can develop the skills and confidence they need.

Dr. Chorney: Our team developed a specialized rehabilitation unit that features high-fidelity simulation labs in which advanced, life-like mannequins approximate everyday care as well as various emergencies that can arise for a child with a tracheostomy. Patients typically transfer to this unit 4-8 weeks before they are discharged and receive aggressive PT, OT, and other therapies to address their developmental needs. Meanwhile, their caregivers practice the skills they’ll need to keep their child safe outside of the hospital setting.

Dr. Gelfand: Education and training make a huge difference. And about five years ago we developed something a little lower-tech: a Pulmonary Sick Plan that is similar to an Asthma Action Plan and helps families discern what can be managed at home and when urgent or emergent care is needed. We were surprised at what a big difference this little plan could make.

What else from the study stood out?

Dr. Afolabi: Social determinants of health often correlate strongly to patient outcomes. We found something heartening within our study cohort: Many of these factors – like race, insurance type, income, single-parent status – did not correlate to patient outcomes.

Social connectedness – which we understand as relating to the strength of a family’s social support network – was the only social determinant of health that correlated to a child’s time to decannulation. It makes sense. These families essentially set up an ICU in their home and their children have very high needs. It can be quite isolating.

Overall, the study shows that no matter who a child is or where they come from, they can have a positive outcome – and we should expect that for them.

Expert, multidisciplinary approach improving care

As a national leader in pediatric pulmonary care, Children’s Health is home to top specialists who treat a high volume of children with challenging long-term conditions like BPD, asthma and cystic fibrosis. Our experience and expertise enable us to give each and every patient the opportunity for their best possible outcome. Multidisciplinary care conferences, comprehensive clinics and inpatient rounding are just some of the ways the team at Children’s Health works together to maximize outcomes for children with lung conditions.

Learn more about BPD care and pulmonology programs at Children’s Health.